Show AWL words on this page.

Show sorted lists of these words.

|

For another look at the same content, check out the video on YouTube (also available on Youku). There is a worksheet (with answers and teacher's notes) for this video.

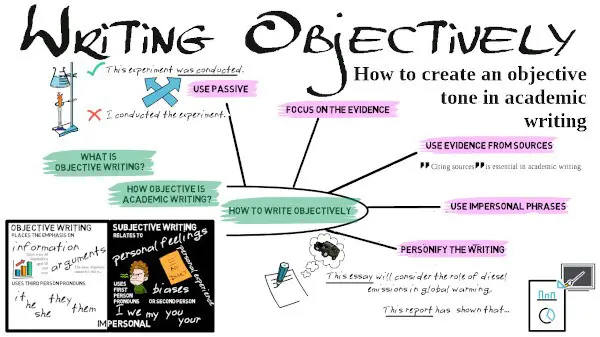

Academic writing is generally impersonal and objective in tone. This section considers what objective writing is, how objective academic writing is, then presents several ways to make your writing more objective. There is also an academic article, to show authentic examples of objective language, and a checklist at the end, that you can use to check the objectivity of your own writing.

What is objective writing?

Objective writing places the emphasis on facts, information and arguments, and can be contrasted with subjective writing which relates to personal feelings and biases. Objective writing uses third person pronouns (it, he, she, they), in contrast to subjective writing which uses first person pronouns (I, we) or second person pronoun (you).

How objective is academic writing?

Podcast is loading. Too slow? Click here to access.

Podcast is loading. Too slow? Click here to access.

Although many academic writers believe that objectivity is an essential feature of academic writing, conventions are changing and how much this is true depends on the subject of study. An objective, impersonal tone remains essential in the natural sciences (chemistry, biology, physics), which deal with quantitative (i.e. numerical) methods and data. In such subjects, the research is written from the perspective of an impartial observer, who has no emotional connection to the research. Use of a more subjective tone is increasingly acceptable in areas such as naturalist research, business, management, literary studies, theology and philosophical writing, which tend to make greater use of qualitative rather than quantitative data. Reflective writing is increasingly used on university courses and is highly subjective in nature.

How to write objectively

There are many aspects of writing which contribute to an objective tone. The following are some of the main ones.

Use passive

Objective tone is most often connected with the use of passive, which removes the actor from the sentence. For example:

- The experiment was conducted.

I conducted the experiment.

- The length of the string was measured using a ruler.

I measured the length of the string with a ruler.

Most academic writers agree that passive should not be overused, and it is generally preferrable for writing to use the active instead, though this is not always possible if the tone is to remain impersonal without use of I or other pronouns. There is, however, a special group of verbs in English called ergative verbs, which are used in the active voice without the actor of the sentence. Examples are dissolve, increase, decrease, lower, and start. For example:

- The white powder dissolved in the liquid.

I dissolved the white powder in the liquid.

The white powder was dissolved in the liquid.

- The tax rate increased in 2010.

We increased the tax rate in 2010.

The tax rate was increased in 2010.

- The building work started six months ago.

The workers started the building work six months ago.

The building work was started six months ago.

Focus on the evidence

Another way to use active voice while remaining objective is to focus on the evidence, and make this the subject of the sentence. For example:

- The findings show...

- The data illustrate...

- The graph displays...

- The literature indicates...

Use evidence from sources

Evidence from sources is a common feature of objective academic writing. This generally uses the third person active. For example:

- Newbold (2021) shows that... He further demonstrates the relationship between...

- Greene and Atwood (2013) suggest that...

Use impersonal constructions

Impersonal constructions with It and There are common ways to write objectively. These structures are often used with hedges (to soften the information) and boosters (to strengthen it). This kind of language allows the writer to show how strongly they feel about the information, without using emotive language, which should be avoided in academic writing.

- It is clear that... (booster)

- It appears that... (hedge)

I believe that...

- There are three reasons for this.

I have identified three reasons for this.

- There are several disadvantages of this approach.

This is a terrible idea.

Personify the writing

Another way to write objectively is to personify the writing (essay, report, etc.) and make this the subject of the sentence.

- This essay considers the role of diesel emissions in global warming.

I will discuss the role of diesel emissions in global warming.

- This report has shown that...

I have shown that...

Summary

In short, objective writing means focusing on the information and evidence. While it remains a common feature of academic writing, especially in natural sciences, a subjective tone is increasingly acceptable in fields which make use of qualitative data, as well as in reflective writing. Objectivity in writing can be achieved by:

- using passive;

- focusing on the evidence (The findings show...);

- referring to sources (Newbold (2021) shows...);

- using impersonal constructions with It and There;

- using hedges and boosters to show strength of feeling, rather than emotive language;

- personifying the writing (This report shows...).

References

Bailey, S. (2000). Academic Writing. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer

Bennett, K. (2009) 'English academic style manuals: A survey', Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 8 (2009) 43-54.

Cottrell, S. (2013). The Study Skills Handbook (4th ed.), Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Hinkel, E. (2004). Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc Publishers.

Hyland, K. (2006) English for Academic Purposes: An advanced resource book. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jordan, R. R. (1997) English for academic purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Example article

Below is an authentic academic article. It has been abbreviated by using the abstract and extracts from the article; however, the language is unchanged from the original. Click on the different areas (in the shaded boxes) to highlight the different objective features.

Title: Obesity bias and stigma, attitudes and beliefs among entry-level physiotherapy students in the Republic of Ireland:

a cross sectional study.

Source:: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031940621000353

Objective

To explore entry-level physiotherapy students’ attitudes and beliefs relating to weight bias and stigmatisation in healthcare.

Background

Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the prevailing view of healthcare professionals

appears to be that obesity is a choice that can be reversed by

voluntary decisions to eat less and exercise more [1], [2].

Existing literature reports that physicians and other healthcare professionals

perceive people with obesity as undisciplined, lazy, weak-willed and unlikely to comply with treatment or make lifestyle changes

[3], [4], [5].

These assumptions

have been shown to result in

multiple negative encounters for patients living with obesity, one of which is experiencing weight bias and stigma at the hands of their healthcare providers [2].

Methods

All final year physiotherapy students in the Republic of Ireland were invited to participate.

Each received a questionnaire, consisting of 72 questions. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were used to analyse the data.

Results

A response rate of 83% (179/215) was achieved. Whilst physiotherapy students, overall, had a positive attitude towards people with obesity,

29% had a negative attitude towards people with obesity, 24% had a negative attitude towards managing this population and most (74%) believed

obesity was caused by behavioural and individual factors.

Over one third of students (35%) reported that they would not be confident in managing patients with obesity and more than half (54%) felt treating patients with obesity was not worthwhile.

Fig. 1 illustrates the findings in relation to physiotherapy students’ perceptions of weight bias expressed by peers, educators and healthcare

professionals in the clinical environment. Almost all students (96%) felt it was unacceptable to make jokes about patients living with obesity.

40% of students perceived their peers as having negative attitudes towards obesity, with 45% having witnessed other students making jokes about patients with obesity.

Fig. 1 illustrates the findings in relation to physiotherapy students’ perceptions of weight bias expressed by peers, educators and healthcare

professionals in the clinical environment. Almost all students (96%) felt it was unacceptable to make jokes about patients living with obesity.

40% of students perceived their peers as having negative attitudes towards obesity, with 45% having witnessed other students making jokes about patients with obesity.

Discussion

This national cross-sectional survey found that obesity bias and stigmatisation are significant issues amongst

physiotherapy students. Almost one third had a negative attitude towards people with obesity, a quarter had a negative attitude towards managing people

with obesity and the majority believed obesity was caused by behavioural and individual factors.

Alarmingly, more than half of the students felt treating patients with obesity was not worth their time.

These findings highlight the disparity between physiotherapy students’ knowledge and beliefs relating to causes of obesity and

current scientific knowledge regarding mechanisms of body-weight regulation.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary findings to suggest that weight stigma-reduction efforts

are warranted for physiotherapy students.

Helping students to understand that obesity is a complex, chronic condition

might be the

first step towards dispelling these negative attitudes towards patients living with obesity.

It is essential, going forward, that clinical educators make an intentional effort to be positive role models when it comes to the management of patients with obesity.

Inclusion of a formal obesity curriculum

should perhaps now be part of the contemporary physiotherapy students’ education.

However, it must be noted that changing the curriculum is only one important step towards changing the student physiotherapist's attitudes

and beliefs towards patients living with obesity. A multipronged approach to implementing this change demands commitment on a professional, clinical, research and educational level.

References

| [1] | Ending weight bias and the stigma of obesity Nat Rev Endocrinol, 16 (5) (2020), p. 253 |

| [2] | F. Rubino, R.M. Puhl, D.E. Cummings, R.H. Eckel, D.H. Ryan, J.I. Mechanick, et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity Nat Med, 26 (4) (2020), pp. 485-497 |

| [3] | J. Seymour, Jl Barnes, J. Schumacher, Rl. Vollmer A qualitative exploration of weight bias and quality of health care among health care professionals using hypothetical patient scenarios Inquiry, 55 (2018), Article 46958018774171 |

| [4] | S.M. Phelan, D.J. Burgess, M.W. Yeazel, W.L. Hellerstedt, J.M. Griffin, M. van Ryn Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity Obes Rev, 16 (4) (2015), pp. 319-32 |

| [5] | J.A.M.M. Sabin, B.A. Nosek Implicit and explicit anti-fat bias among a large sample of medical doctors by BMI, race, ethnicity and gender PLoS One, 7 (2012), Article e48448 |

Checklist

Below is a checklist for using objectivity in academic writing. Use it to check your writing, or as a peer to help. Note: you do not need to use all the ways given here.

| Item | OK? | Comment |

| The writing is objective in tone. | ||

| The writing uses passive to avoid personal pronouns (e.g. The experiment was conducted). Passive is not overused. | ||

| The writing focuses on the evidence (e.g. The findings show...). | ||

| The writing uses evidence from sources and third person pronouns (e.g. Newbold (2021) shows that... He further demonstrates...). | ||

| The writing uses impersonal constructions with It and There. | ||

| The writing uses personification (e.g. This report has shown). |

Next section

Read more about writing critically in the next section.

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about using complex grammar.